There is an oft-quoted (and perhaps apocryphal or fabricated) statistic that business acquisitions have the same failure rate as startups. A quick Google reference for me neither confirms nor denies. However, that general rule is that most acquisitions certainly do not yield the intended or pretended synergies the internal buy-side M&A peddlers initially promulgate. In fact, the opposite has been the unfortunate reality: many acquisitions fail to deliver as promised or simply fail altogether.

There is no catch-all list of all the reasons acquisitions fail, but personal experience has certainly proven illuminating as to some of the bigger unforeseen boulders inherent in nearly any buy-side strategy.

Rational Pricing Theory & Seeking Alpha

The first mistake most business buyers make is thinking they have something proprietary in their strategy. This error is most apparent in the myriad of non-strategic private equity buyers.

Why is this important to understanding failure? A proprietary process assumes at least one of two things holds true, either:

- You have the ability to source and close (two different things) “not-for-sale” businesses which inherently assumes you can acquire at below-market valuations, thus making a huge portion of your gains in the buy.

- In a post-close scenario, your team will be significantly–not just marginally–better at running the business than the current ownership.

Let’s break down the fallacies of both assumes in sequence:

First, assuming you can source better than every other strategic and financial buyer, including hundreds (and perhaps thousands) of private equity groups and family offices is presumptuous at best. It’s the age-old problem amid society in general of illusory superiority. That is, when >50% of the population believes they are smarter than most people, someone is living a fallacy.

It also assumes you can truly find the needle-in-the-haystack acquisitions whist everyone else is combing through the same proverbial haystack. From my experience, truly off-market targets take a great deal more time to both source and close. Primary difficulties there include a lack of company preparation on the part of an engaged investment banker on the sell-side.

In other words, the gains you could of extracted out of a fund are often eaten up by the unfriendly character of time. If it takes you XX months longer to get proprietary deals, you may lose fund returns to your LPs (or shareholders) you could have gained had you just paid market prices and started gleaning cash-flows from an existing target sooner.

Further still is the assumption that the rational pricing model does not exist in middle and lower middle-market deals. In other words: there is no such thing as a good deal. This is more true in today’s liquid private equity market than ever. Buyers are paying market rates for targets and market rates are up…way up.

Second, once you do pay market rate for the acquisition–and you most likely will–you then assume that your gains are now to be gleaned from improved operations above and beyond existing ownership and management. True, outsiders will see through a different lens and likely can add value, especially if they are willing to invest greater resources into the growth of the business, assuming 1+1=3–But, inherent operational and execution risks bar a potential acquirer from really gleaning synergies or growth out of an acquisition.

The most successful buyers in off-market deals find companies with passive or constrained management that need rescued, but such deals are far between.

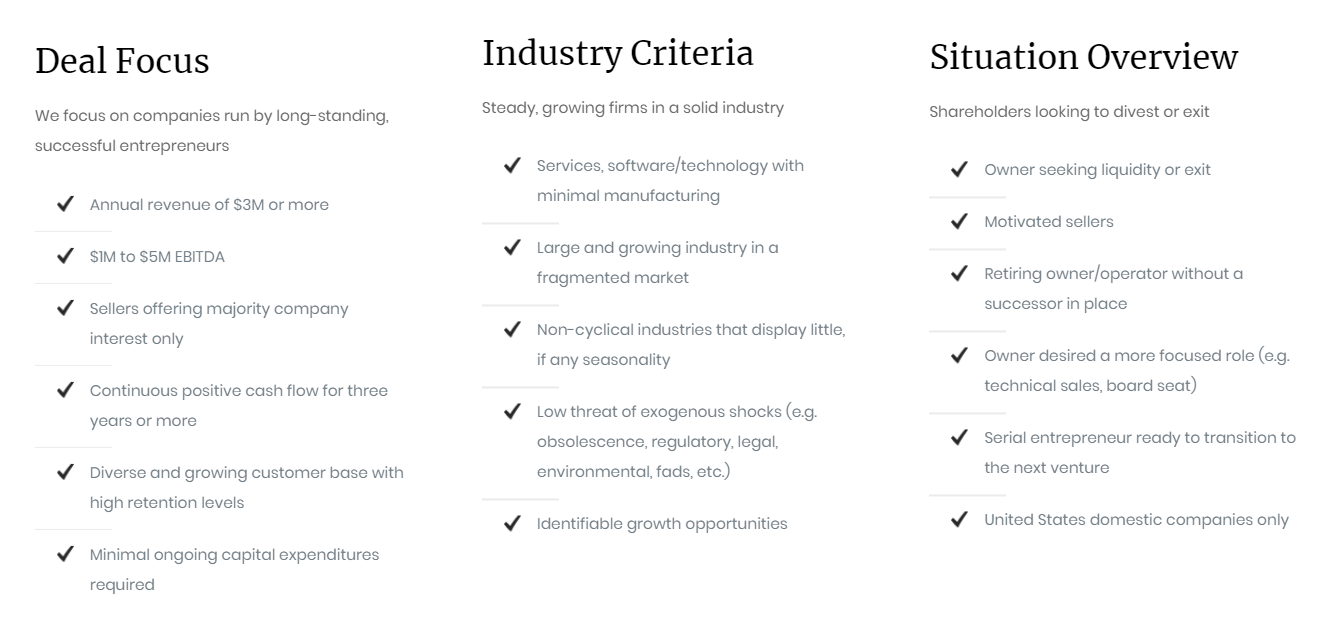

Moreover, how much differentiation is there among competing, middle-market private equity firms? Take a look at these considerations, from the private equity section of our website and tell me if the sound like a photocopy of every other PEG on the market:

Strategy differentiation among varying financial buyers has become more and more difficult. In fact, I would wager that every newly-minted PEG regresses more to the mean in both LP/GP structure, sourcing strategy AND post-acquisition operations. Vast competition makes differentiation that much more difficult.

Operations: Real Estate vs. Private Equity

Differing companies, industries and their transactions have varying degrees of difficulty and complexity. I can recall a few years back working on a transaction where the seller’s business operated in a sizable commercial property also owned in a separate entity by the seller.

When fair-market offers for the business started to flow-in, the business owner asked, puzzled at the thought:

I cannot simply understand how my highly-profitable business is worth less than the real estate in which it operates.

First off, it’s Seattle. Secondly, and this is the best non-quantitative reason to explain this disparity: it’s so much easier to wreck a private equity acquisition than a real estate acquisition.

Even the most professional, experienced buyers may not be prepared for some of the subtle nuances that separate a successfully operating and profitable company from one that may soon be out of business.

Business Valuation Gaps

Proprietary strategy aside, business valuation expectations between savvy buyers and sellers who think Facebook transaction valuations are representative of real-world deal-making can be difficult to say the least. In most deals (at least in my personal experience representing sellers and buyers), it’s the sellers whose expectations are outside of reason. In the middle market and below, business buyers are more frequently in the business of acquiring while sellers often transact perhaps once or twice in their lifetime. That is perhaps the biggest reason you see transaction advisors more often on the sell-side of an M&A deal (that–and if we’re being transparent–the fees are typically higher on the sell-side).

In short, business buyers may be willing to pay what they deem as fair per the market, while business sellers think their business is worth 10x revenue even in a down market. Fortunately, multiple offers from a rational market typically help to quell any blue sky thoughts of seller grandeur.

Incidentally, we have covered before the rationality of using real estate cap rates (or at least SBA financing) as a barometer for business valuations and cooling business valuation expectations among business sellers. It’s at least one of the gaps that is needed to be bridged between buyers and sellers when the difficult discussions on price start to occur.

The Myopic View of Due Diligence

Unfortunately, most middle-market M&A advisors on the buy-side are frequently so focused on getting the deal across the finish line that post-merger integration becomes an unfortunate afterthought. It could be rightly referred to as the a myopic view through the lens of due diligence.

And why wouldn’t an investment banker be focused on this goal? Isn’t s/he incentivized by the contingency of a buy-side success fee? Unfortunately, I would compare the lack of post-merger integration planning to the shortsightedness of operating public companies who invest for short-term gains only.

In the case of most would-be and especially first-time buyers, it’s not even a case of getting through the honeymoon stage. It’s more a case of doing a deal and not performing an acquisition. There is a big difference.

Countless books, lectures and even Harvard Case Studies have covered the subject of post-merger integration. We will discuss it more in depth at a later date. However, it still represents the area with the greatest potential of absolutely botching it when it comes to getting a deal done. To be short, post-merger integration is all about people, processes and procedures in varying degrees.

In my personal experience, when it comes to buy-side M&A, most investment bankers are really good at getting a decent or great deal done. It’s the “rubber meets the road” post-merger operations that are most frequently lacking. As a recap:

- Don’t assume you’re better than all the other acquirers out there. Know your limitations and plug the holes with the right transaction, integration and legal assistance possible.

- Go into a transaction expecting to give value for value. If you operate by the zero-sum-game rule, ultimately someone loses. The best deals either end up with both sides feeling that they won or both sides feeling the lost. On the one hand, both felt the deal was fair. On the other, both likely stretched their mental capacity to get to the valuation in which all could agree.

- Plan for post-merger integration. Get the team in place. Have bi-weekly meetings before and during due diligence to discuss integration strategy and planning.

We have not even come close to covering the literally cacophony of areas and means that could put the kibosh on an otherwise good deal (for both sides), but hopefully this proves helpful as you look to assess your own buy-side strategy.

What are some critical areas not listed here that should be included?

And, for the 10% of deal-makers that are able to get it right, please let us know what makes your buy-side targeting so successful.